Prevention ABC: Hamstrings.

- Paweł Krotki-Borowicki

- Sep 7, 2025

- 10 min read

"Prevention is better than cure"—Hippocrates.

The content ahead opens a series of scientific essays devoted to injury prevention in sport.

This article outlines a modern perspective on strategies to reduce the number and severity of the most common muscle injury in football—hamstring injuries—and describes them with reference to a broad, up–to–date and engaging body of sports medicine literature (most of it open access).

Crash analogy

Imagine that—despite the legal requirement—you didn’t fasten your seat belt while driving straight into a solid wall at 30 km/h. At such a speed, slower than many e–scooters, it may seem you could "brace" and absorb the impact with your arms. The problem is that dissipating that momentum over a short distance—say 20 cm—means accepting a load of nearly 18 g over <50 ms—faster than a human can consciously react. Peak forces on the upper limbs in this scenario reach ~3000–3500 N per arm if you assume you're mainly decelerating the trunk, and >6000 N per side if the whole body is involved (not to mention the additional effects of the crumple zone).

For comparison, the maximal isometric pushing force in elite throwing athletes reaches ~1500–2000 N in total, while within the first 50 ms only a fraction is realistically available—closer to 300–600 N per arm ¹. Anyone who works with "forces" daily knows that well–developed eccentric capacity (which brakes motion) can yield much higher values than those reported in that study, but the moral here is simple: an absolute ban on e–scooters!

First things first: force!

The example above reflects a baseline, mechanistic way of thinking about sports injuries.

Epidemiological data show that the majority of critical injuries in team sports are non–contact or arise from repetitive overload ². Observations also suggest they often occur during sudden losses of stability and may be linked to higher–order cognitive deficits, for example: impaired movement anticipation due to fear, attentional overload or prediction errors ³. Each interpretation is true in its own way; yet if we wish to reduce the drama of injury to a single act, the simplest lens is a force–load perspective: the athlete was injured because, at the critical moment, they were not strong enough to apply an efficient, effective resistance ⁴.

This isn’t just an abstract metaphor or a fashionable theory—like the crash example, it's something that can be measured, analysed and translated into practice. Comprehensive injury thinking should rest on solid foundations that then open the door to other, equally important, dynamic and plausible explanations.

Health prevention

From a public–health standpoint, prevention is a set of actions aimed at avoiding the onset of disease and injury, mitigating their course, limiting disability and reducing mortality.

Modern prevention spans four (or more) levels⁵:

0: Primordial—at the source: | I: Primary—most desired: |

Eliminating risk factors at environmental and societal level, i.e. legislation on substances, road speed limits, healthy working conditions, urban planning that supports physical activity. | Preventing disease in healthy people through vaccination programmes, healthy diet, regular physical activity, oral health, health education, and mandatory seat-belt use in cars. |

II: Secondary—diagnostic: | III: Tertiary—medical: |

Early detection through screening (periodic blood tests, mammography, Pap tests, HPV testing, blood pressure measurement, glucose testing, colonoscopy)—ideally at a stage that allows effective treatment. | Preventing recurrences by limiting the consequences of existing disease, including medical rehabilitation, treatment and supporting quality of life in chronic conditions—when cure is not always possible. |

There is also increasing discussion of a fourth level of prevention, i.e., protecting the patient from waste of resources (time, attention, finances) due to over–medicalised protocols, unnecessary tools and training technologies, or alternative medicine—interventions that may do more harm than good ⁶.

Prevention operates at both the individual and system level—covering policy, legislation, environmental and educational actions—and is among the most effective public–health tools for reducing morbidity and premature death. The numbers are clear: in England and Wales, reductions in smoking, cholesterol and blood pressure cut coronary heart disease mortality by >50% over two decades ⁷; after smoke–free legislation, hospitalisations for myocardial infarction fell by ~19% within months⁸; seat–belt mandates reduce the risk of death in a crash by ~45% (and even ~60% in SUVs/pickups) ⁹; vaccination prevents 3.5–5 million deaths annually worldwide ¹⁰.

Prevention—though less spectacular than osteotomies, transplants and treatment—decides the length and quality of life of whole populations.

Prevention in sport

Translating that public–health logic to sport involves similar actions before the first injury and after an injury has occurred (to limit consequences and prevent recurrences). Analogous to the previous framework, sports–medicine prevention includes:

I: Creating a safe training environment and infrastructure—adequate pitch quality, surfaces and footwear; regulations on workload limits and athlete health protection. | II: Actions in healthy athletes to reduce first-injury risk, e.g., eccentric hamstring strengthening, teaching single-leg jumping/landing, and gradual exposure to fast running and sprinting. |

II: Early detection of overload/alert states via observation, history, clinical and biomechanical assessment, MRI, and performance monitoring—before a full injury develops. | III: Limiting consequences of an existing injury through effective rehabilitation, optimal return to sport, and progressive loading to reduce the risk of chronic under-training. |

As in public health, prevention in sport determines the health of a population—only here the population is athletic. Data show that implementing prevention programmes such as FIFA 11+ can reduce injury risk by 30–50% ¹¹, systematic eccentric hamstring strengthening with the Nordic Hamstring Exercise (NHE) can halve hamstring injuries ¹², and progressive Copenhagen Adduction Exercise (CAE) programmes can reduce groin–injury risk by 41% ¹³.

Prevention in sport, while less flashy than max lifts and shock plyos, truly shapes the length and quality of a sporting career.

The prevention sequence

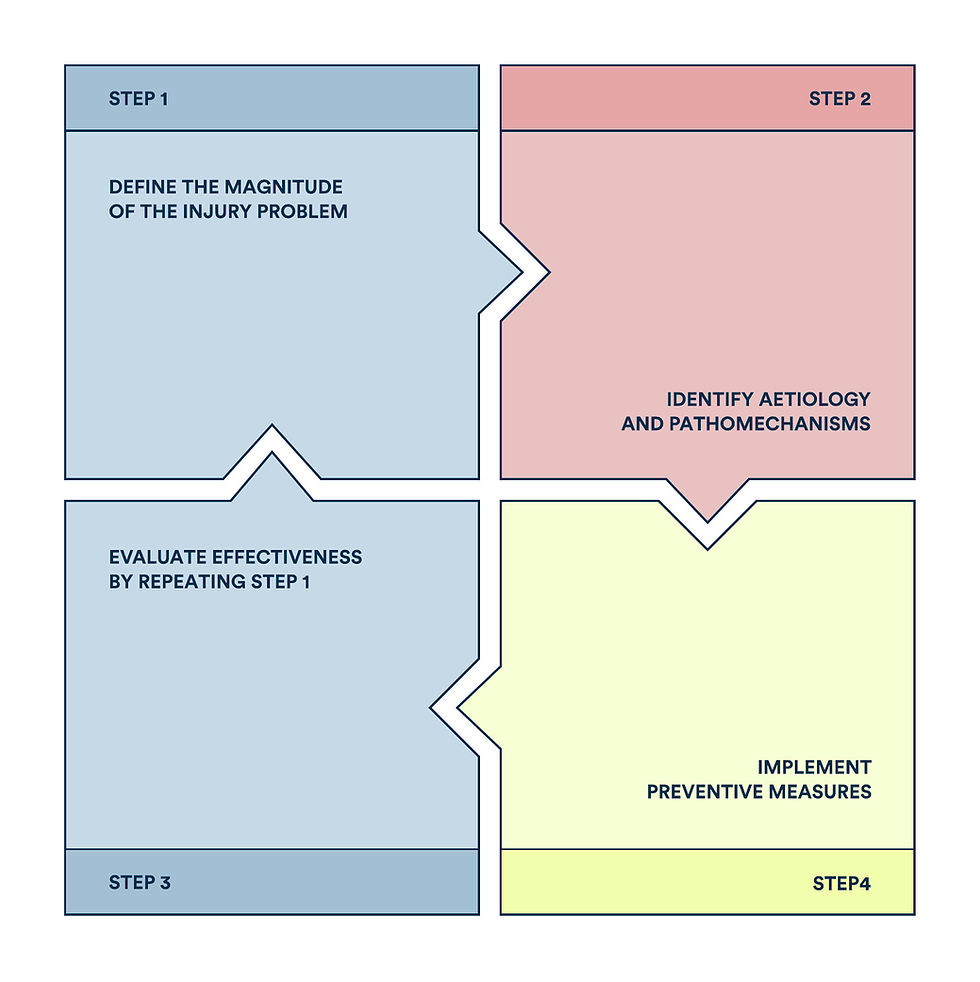

The theoretical backbone—and starting point—for injury prevention thinking remains the four–step model proposed by van Mechelen (1992) ¹⁴, the sequence of prevention: (1) establish the magnitude of the problem (incidence, severity), (2) identify aetiology and mechanisms, (3) introduce preventive measures, and (4) evaluate effectiveness by repeating step 1:

This model still underpins much research, even though in its original form it largely omits the athlete's context. An attempt to broaden its frame came with Bittencourt et al. (2016) ¹⁵, who, alongside "tangible" indicators, included organisational, cultural and environmental factors—the "sport's backstage"—no less important for injury risk than isolated biomechanical parameters:

Diagram 2. Four–step prevention model expanded to include contextual factors (author's adaptation).

Even then, the models have limits. They assume risk factors are sequential and linear, and that prevention can be located close to the instant of injury. While reducing the problem to a moment—shorter than a blink—can be practical, over–simplification may breed the belief that all factors are fully controllable and modifiable, e.g., through strength training and physiotherapy alone.

In reality, causes extend beyond the incident and include organisational, educational, cognitive, behavioural, economic, sport–specific, complex and unknown influences that can indirectly modulate symptoms, intensify pain and raise susceptibility. Their non–linear interrelations are captured by Bolling's et al. "network of determinants" (2018) ¹⁶—an explicitly multi–level view in which many paths can lead to comparable outcomes, much of it shaped by context.

Time to make this concrete with hamstrings—let's leave the highway and step onto the pitch…

Example: hamstring injuries

The most common muscle injury in football is to the hamstrings, accounting for 34% of all muscle injuries¹⁷. The average frequency is 1.29 injuries per 100 athletes per year, and the strongest risk factor is previous hamstring injury, with recurrence rates of 22–34% ¹⁸. Injuries most often occur in the terminal swing phase of running, when the hamstrings work eccentrically to decelerate the shank—the time of greatest susceptibility to tensile stress. The typical mechanism resembles a "sniper shot"—an athlete sprints, then suddenly collapses clutching the back of the thigh¹⁹. The injury usually involves the myotendinous junction (MTJ), often in the distal third of the thigh, with the biceps femoris long head (BFlh) dominating (66–87% of HS injuries) ²⁰. Video analyses show that 70–81% of injuries occur during high–speed running or sprinting²¹, and 36% involve the proximal tendon of the singletendon BFlh. HS injuries arise from running alone (21%), stretching alone (36%), but most often from mixed tasks combining sprint+stretch (43%), rooted in dynamic running with changes of direction (29%) and kicking (29%) ²². By severity, ~57% are grade I (mild), ~27% grade II (moderate) and ~3% grade III (severe) ²³. Mean timeloss is 17–21 days, but severe, extensive injuries—unlucky cases involving BFlh "T–junction" architecture—are associated with much longer returns (often >3 months) ²². |

Hamstring injuries can thus be framed as exceeding the load–bearing capacity of tissue—when external load outstrips the system’s ability to absorb it. Biomechanical work shows hamstring tissue sustain clear damage at 300–1200 N ²⁴, while low eccentric strength (<~300 N per limb, especially at longer muscle lengths) quadruples injury risk ²⁵. Crucially, no gym exercise loads the hamstrings as intensely as sprinting. Heavy resistance exercises typically elicit only 55–85% MVC compared with all–out sprinting ²⁶—hence sprint exposure should be accounted for when designing sport–specific prevention.

Beyond "force accounting", qualitative observations matter—e.g., individual HSR technique. Mendiguchia et al. (2024) showed that increased anterior pelvic tilt (APT) adds hamstring lengthening, as much as >1 cm proximally per 5° APT ²⁷; clinically, higher APT is associated with increased injury frequency ²⁸.

In practice, we should ask which "determinants" of HS injury are modifiable (and which are not) and select tools accordingly. A guiding principle—simplicity and scalability, much like vaccination. The NHE targets key risks: deficits in eccentric strength, short fascicles and increased muscle stiffness. It is then supplemented with corrective/conditioning elements that rehearse "worst–case scenarios" and the sport's final demands, e.g., curved sprinting (with trunk rotation).

Final verdict

The debate over the effectiveness of prevention programmes remains lively, especially for hamstring injuries, whose absolute numbers continue to rise²⁹. Yet today's football and other team sports impose far greater physical demands—more sprints, HSR efforts, decelerations and contacts than a decade ago.

Viewed relatively, the picture changes: regular sprint sessions at ≥80–90% MSS combined with eccentric training can reduce HS injury risk by 56–94% ³⁰; stable training loads matter—sudden spikes in ACWR markedly increase injury susceptibility ³¹; over longer horizons, comprehensive programmes blending strength, agility and flexibility have produced spectacular results, cutting HS injuries from 138 to just 7 per season in sprinters ³². Moreover, the relation between HSR and injury is U–shaped: too little or too much raises risk, while an optimal weekly range (701–750 m) is protective³³. |

|---|

Taken together, despite rising absolute counts, and relative to escalating demands of modern sport, evidence–based work by medical and coaching staffs is paying off—more effective than sole "Nordics–Only" routines.

Prevention isn't an illusion; it’s an investment in health—priceless in sport and in life.

Further reading:

Augustsson J et al. Relationship Between Early and Maximal Isometric Upper–Body Push and Pull Force Production Among Elite Female and Male Swedish Track and Field Throwers. Sports (Basel) (2025)—OPEN ACCESS.

Bahr R et al. Understanding Injury Mechanisms: A Key Component of Preventing Injuries in Sport. British Journal of Sports Medicine (2005).

Darren P. Reconstructing Cognitive Function Following ACL Injury. Aspetar Sports Medicine Journal (2020)—OPEN ACCESS.

Hewett TE at al. Preventive Biomechanics: A Paradigm Shift with a Translational Approach to Biomechanics. The American Journal of Sports Medicine (2019)—OPEN ACCESS.

Kumar S et al. Health Promotion: An Effective Tool for Global Health. Indian Journal of Community Medicine (2012).

Martins C et al. Quaternary Prevention: Reviewing the Concept. European Journal of General Practice (2018)—OPEN ACCESS.

Unal B et al. Explaining the Decline in Coronary Heart Disease Mortality in England and Wales between 1981 and 2000. Circulation (2004)—OPEN ACCESS.

Mackay DF et al. Meta–Analysis of the Effect of Comprehensive Smoke–Free Legislation on Acute Coronary Events. Heart (2010).

Dane z US Department of Transportation i Insurance Institute for Highway Safety (2015)—OPEN ACCESS.

World Health Organization. Immunization Coverage–Key Facts. WHO (2023).

Al Attar WSA. The FIFA 11+ Injury Prevention Program Reduces the Incidence of Knee Injury Among Soccer Olayers: A Systematic Review and Meta–Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport (2022).

van Dyk N et al. Including the Nordic Hamstring Exercise in Injury Prevention Programmes Halves the Rate of Hamstring Injuries: A Systematic Review and Meta–Analysis of 8459 athletes. British Journal of Sports Medicine (2019).

Harøy J et al. The Adductor Strengthening Programme Prevents Groin Problems Among Male Football Players: A Cluster–Randomised Controlled Trial. British Journal of Sports Medicine (2019).

van Mechelen W et al. Incidence, Severity, Aetiology and Prevention of Sports Injuries. A Review of Concepts. Sports Medicine (1992).

Bittencourt NFN et al. Complex Systems Approach for Sports Injuries: Moving From Risk Factor Identification to Injury Pattern Recognition: Narrative Review and New Concept. British Journal of Sports Medicine (2016)—OPEN ACCESS.

Bolling C et al. Context Matters: Revisiting the First Step of the ‘Sequence of Prevention’ of Sports Injuries. Sports Medicine (2018)—OPEN ACESS.

Garcia AG et al. Hamstrings Injuries in Football. Journal of Orthopaedics (2022)—OPEN ACCESS.

Gudelis M et al. Epidemiology of Hamstring Injuries in 538 cases from an FC Barcelona Multi–Sports Club. The Physician and Sportsmedicine (2024)—OPEN ACCESS.

Danielsson A et al. The Mechanism of Hamstring Injuries—A Systematic Review. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders (2020)—OPEN ACCESS.

Bucci D et al. Hamstrings Injuries with MRI Findings in a Major League Soccer Team. Archives of Orthopaedics (2020)—OPEN ACCESS.

Jokela ABM et al. Mechanisms of Hamstring Injury in Professional Soccer Players: Video Analysis and Magnetic Resonance Imaging Findings. Clinical Journal of Sports Medicine (2023)—OPEN ACCESS.

Wing C et al. Hamstring Strain Injuries: Incidence, Mechanisms, Risk Factors, and Training Recommendations. Strength and Conditioning Journal (2020)—OPEN ACCESS.

Kerin F et al. Are All Hamstring Injuries Equal? A Retrospective Analysis of Time to Teturn to Full Training Following BAMIC Type 'C' and T–Junction Injuries in Professional Men's Rugby Union. Scandinavian Journal of Medicine & Science in Sports (2024)—OPEN ACCESS.

MacLeod et al.Proximal Hamstring Repairs Demonstrate Similar Load to Failure as Intact Hamstring Tendons: A Systematic Review and Meta–Analysis. Arthroscopy, Sports Medicine, and Rehabilitation (2025).

Shah S et al. The Influence of Weekly Sprint Volume and Maximal Velocity Exposures on Eccentric Hamstring Strength in Professional Football Players. Sports (Basel) (2022).

Bourne MN et al. Impact of Exercise Selection on Hamstring Muscle Activation. British Journal of Sports Medicine (2017).

Mendiguchia J et al. Anterior Pelvic Tilt Increases Hamstring Strain: A Cadaveric Investigation. Knee Surgery, Sports Traumatology, Arthroscopy (2024).

Bayrak A et al. Increased Anterior Pelvic Tilt Angle Elevates the Risk of Hamstring Injuries in Soccer Players: A Prospective 5–Year Study. Research in Sports Medicine (2025).

Ekstrand et al. Hamstring Injury Rates Have Increased During Recent Seasons and Now Constitute 24% of All Injuries in Men’s Professional Football: The UEFA Elite Club Injury Study from 2001/02 to 2021/22. British Journal of Sports Medicine (2023)—OPEN ACCESS.

Tedeschi J et al. Sprint Training for Hamstring Injury Prevention: A Scoping Review. Sports Health (2025)—OPEN ACCESS.

Rogalski B et al. The Influence of Acute:Chronic Workload Ratios on Injury Risk in Elite Athletes. Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport (2017)—OPEN ACCESS.

Sugiura Y et al. Prevention of Hamstring Injuries in Collegiate Sprinters. Orthopaedic Journal of Sports Medicine (2017)—OPEN ACCESS.

Malone S et al. High–Speed Running and Sprinting as an Injury Risk Factor in Soccer: Can Well–Developed Physical Qualities Reduce the Risk? Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport: Home Page (2018).

Enhance the discussion:

Respond to the ideas included in the test by writing to: me@pawelkrotki.com.